Digital media are becoming more common in classrooms around the world. The underlying pedagogy and design of curricula determine the benefits to students. Picture credit: Northeastern University

Introduction

The TPCK (also known as TPACK) Model of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge, originally proposed by Misrah and Koehler (Koehler & Mishra, 2005, 2008, Misrah & Koehler, 2006), has taken the academic world by storm by proposing a pragmatic and systematic theoretical grounding to assist teachers integrating content knowledge, pedagogy and technology.

The model was developed by the authors during a five-year cooperation with American K-12 teachers and the faculty of Michigan State University. Its theoretical foundation is based on Shulman’s concept of pedagogical content knowledge, in short PCK (Shulman, 1986, 1987). At the heart of PCK stands the intuitive argument that in order for teachers being able to render content knowledge (CK) accessible to their students, it is a prerequisite for them to transform content knowledge in a pedagogically sensible manner (P), integrating both expert content and pedagogical knowledge. To their credit, Misrah and Koehler pointed out that professional organizations such as the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA, 1999) and National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE, 2001) acknowledged the value of PCK for teacher preparation and teacher professional development.

Description of the TPCK Model

The authors gradually extended Shulman’s model by the component of technology (T), translating it into what is known today as the TPCK (or TPACK) model. How does this model work?

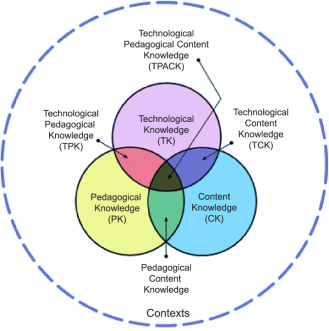

Graphic: A visualisation of TPACK

Using Shulman’s metaphor of three overlapping circular domains, the model concludes a total of seven key areas of knowledge. Beyond the technological, pedagogical- and content knowledge (the body of expert knowledge about a subject matter), four new areas come into play:

Technology Knowledge (TK) is defined by the authors as the teacher’s ability to use and apply digital technology in the classroom.

Technological Content Knowledge (TCK) relates to how technology shapes and influences the representation of content. Recent examples would be, e.g., the examination of phenomena by statistics, predictive analytics or computer simulations, opening new ways of exploring the world that was not available prior to the advent of digital technology.

Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK) is defined by Misrah and Koehler as the pedagogical knowledge about the educational benefit of digital tools. The authors cite as examples digital class record systems, online grading, discussion boards and chat rooms.

Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK), finally, as the cross-section of all areas ”… is the basis of good teaching with technology and requires an understanding of the representation of concepts using technologies; pedagogical techniques that use technologies in constructive ways to teach content; knowledge of what makes concepts difficult or easy to learn and how technology can help redress some of the problems that students face; knowledge of students’ prior knowledge and theories of epistemology; and knowledge of how technologies can be used to build on existing knowledge and to develop new epistemologies or strengthen old ones.” (2006, p. 1029.)

A Critical Reading of the Original Script

The original script contains two segments. The first describes the TPACK model, as outlined above, while the second segment was named ‘APPLYING THE TPCK FRAMEWORK TO PEDAGOGY’. This section advocates what is typically described in the literature as design thinking (Brown & Katz, 2009; Lietka et al., 2017; Plattner et al., 2016; Rowe, 1998). Mishra and Koehler define their approach explicitly as ‘learning technology by design’ (p. 1034).

In this application part, the authors forward some valid points that are typically conceptualized in constructivist pedagogy. These arguments consist of notions such as

- Technology changes fast, which is why teachers need to be able to update their skills, classroom content and mode of delivery continuously. This argument also entails (contradicting TPACK) that learners cannot primarily rely on content that is easily outdated, advocating the development of process skills to make appropriate content available and to relate facts with changing ideas and complex concepts.

- Learning happens in situated contexts, which is why digital technology needs to support the age of learners and their developmental needs, the type of school or a variety of individual learning styles. In design thinking, this notion is complemented by taking a user- or human-centred approach. This entails that pedagogy is not arbitrary as well.

- Competencies need to be developed: A mere wish-list of competencies does not tell teachers on how to achieve them. TPACK promises a structured approach to guide implementation.

On face value, the TPACK model appears intuitive in stating technology, content and pedagogy as the main drivers of education. Similarities to theories such as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs or Bloom’s Taxonomy arise in so far, as an additive modular framework is proposed to explain and guide the complex dynamics of learning processes. TPACK seems to intuitively answer to all potential combinations of its components by starting with simplified assumptions.

A closer view, however, reveals that TPACK rests on a number of problematic assumptions:

- Isolated domains: The first assumption is that technology, pedagogical- and content knowledge exists in isolation and can be understood by relating them via distinct overlapping circles as a representation of empirical reality. The second reading of this first assumption is that technological, content- and pedagogical knowledge exists as an a priori construct, each type of knowledge separated from the learning processes of involved actors. Shulman’s original categorical distinction between pedagogical and content knowledge was not further questioned by Misrah and Koehler. Citing McEvan & Bull (1991) and Segall (2004), Archambault and Barnett (2010) pointed out that ‘content, in the form of scholarship, cannot exist without pedagogy, and (…) explanations of concepts are inherently pedagogical in nature.’ (p. 1657). To this extent, Shulman’s framework appears to unnecessarily complicate the reciprocal relationship between content knowledge construction and the corresponding metacognitive reflection (pedagogical knowledge) that accommodates and frames it. Adding technology to the equation does not solve the initial lack of construct validity.

- The dominance of content knowledge: The second assumption is that content knowledge (CK) represents one of the main components of digital- or media-education and should be regarded as one of the main educational concerns. It is not elaborated and justified why and how that is. Modern pedagogy is concerned about the acquisition of competencies, personal resources and process skills, but not content per se. Content is framed by overarching concepts and therefore cannot be separated from discoursive epistemological access.

- A Model without actors and goals in mind: The third assumption is that the placing of abstracted thematic blocks (T, P and CK) is the most appropriate manner to plan learning and teaching activities with and about digital media. By excluding the actors of learning processes from the model (teachers, facilitators, students or the school administration), TPACK is not developed as a student-centred framework, which should be a grave concern for any educator.

The Design Thinking Conundrum

The TPACK application section focusses on design thinking which is, by definition and its human (learner)-centered approach, constructivist in nature. Typical issues of design thinking do not deal with content dissemination, but problem-solving, the development of innovative and novel solutions to challenges, the creation of new knowledge and ideas. Design thinking is about facilitating testable hypotheses as well as developing and improving ways of communication and group collaboration. There appears to be an internal contradiction and gap in the approach suggested by Misrah and Koehler; this is to build on a teacher-centered model based on content dissemination on one hand and to promote design thinking, which is based on active self-directed learning, on the other. There is neither a clear explanation given nor a discussion facilitated by this significantly different and incompatible choice of philosophies. The elephant standing in the room is the role of constructivist pedagogy. Since the TPACK model had been originally developed in collaboration with K-12 teachers, it is likely that teacher-centred pedagogy was assumed as the default model whereby design thinking was added on as a technological-compatible, convenient afterthought.

In a blog post, Punya Misrah answered when asked about Problem-based Learning (PBL) as follows: “There is a value to small group activities as there is to a lecture. Clearly if we are emphasizing higher order thinking skills – we need to move away from simple rote-learning tasks. It is just that TPACK per se does not lean one way or the other. It does not speak to the broader goals of education. Some of my more recent work has focussed on these broader goals – and in that there are many areas (if not all) that we will be in agreement. Finally, TPACK does not privilege content, technology or pedagogy. In fact we have argued (quite clearly) that there are situations where one or the other is the driver.”

Misrah states unequivocally that TPACK is not a goal-oriented model. Educators may find an issue with the argument of taking a neutral stand on pedagogy. If we seek to educate strong self-directed, lifelong learners that build in intrinsic motivation in order to thrive in a digitized and globalized society 4.0, then a merely instructional or a behavioristic approach is not an option. Given that the goal of education is the empowerment of learners of all ages, TPACK cannot have it both ways.

Mishra is also wrong assuming an arbitrary relationship between pedagogy and technology. Empirical research has demonstrated that teacher-centred instructors use technology in significantly different ways as compared to instructors willing to change form and content of curricula via digital media or colleagues who have embraced constructivist forms of pedagogy (Schaumburg, 2003). His mention of online discussions as an example of technology driving pedagogy is not correct insofar e.g., teachers advocating rote-learning would simply not bother using online chats to disrupt their practice. It is the pedagogical attitudes of teachers that determine the use of technology in the classroom, not vice versa. Technology is not neutral in this regard since technology either supports or distracts from facilitating learning processes and achieving learning outcomes. In an arbitrary framework that facilitates any system, there can be no definite criteria for the usefulness or quality of digital media.

Conclusion: TPACK’s Lack of Empirical Support and Scientific Usefulness

While some academics find in TPACK a universal model for curricula design, teachers in the field may find it cumbersome, misleading and confusing to sort out the finer details of TK, PK, CK, TPK, PCK, TCK and TPACK in order to progress with the design of learning units. In their empirical study comprising 596 online teachers across the United States, Archambault and Barnett (2010) could not verify pedagogy, content and technology as three separate domains. The only domain that distinguished itself from the others was technology.

As expected, teachers struggled with making clear inferences to the overlapping fields. The authors specified the following example: “Three online teachers were challenged with separating out specific issues of content and pedagogy. For example, Item d – “My ability to decide on the scope of concepts taught within my class” was interpreted by two teachers as belonging to the domain of pedagogical content rather than content alone. The same misinterpretation happened with Item b – “My ability to create materials that map to specific district/ state standards.” The participants saw this item as a part of pedagogy content (Archambault & Crippen, 2009). These examples, coupled with the results from the factor analysis, support the notion that TPACK creates additional boundaries along and already ambiguous lines drawn between pedagogy and content knowledge.” (p. 1659)

TPACK, to state the obvious, is not a theory that can be empirically verified. There are no dependent or independent variables defined (since all components are regarded as equal with no clear causal or conditional relationships implied), there are no null-hypotheses to test and there are no evidence-based outcomes to predict. TPACK failed in initial empirical research distinguishing its seven mutually separated domains. Most worryingly, however, the model offers neither a goal-directed framework that is concerned with the empowerment of learners in the use of digital technology, nor is it concerned about the effects of digital socialization trajectories on society.

It still needs to be demonstrated that the positive effects attributed to TPACK are inherent effects of the model and not based on the critical reflections that are bound to come up when educators discuss the integration of digital media for the classroom.

References

Archambault, L.H. & Barnett J.H. (2010). Revisiting pedagogical content knowledge: Exploring the TPACK framework. Computers & Education, 55 (2010) 1656–1662

Brown, T., & Katz, B. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking can transform organizations and inspire innovation. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2005). What happens when teachers design educational technology? The development of technological pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 32(2), 131–152.

Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2008). Introducing TPCK. In AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology. (Ed.), Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK). New York: Routledge.

Liedtka, J., Salzman, R., & Azer, D. (2017). Design thinking for the greater good. New York: Columbia University Press.

McEwan, H., & Bull, B. (1991). The pedagogic nature of subject matter knowledge. American Educational Research Journal, 28(2), 316–334.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: a framework for integrating technology in teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. (2001). Professional standards for the accreditation of schools, colleges, and departments of education ([Electronic version]. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved June 27, 2004, from http://www.ncate.org/2000/2000stds.pdf

National Science Teachers Association. (1999). NSTA standards for science teacher preparation [Electronic version]. Arlington, VA: Author. Retrieved June 28, 2004, from http://www.iuk.edu/faculty/sgilbert/nsta98.htm

Plattner, H., Meinel, C., & Leifer, L. J. (2016). Design thinking research: Making design thinking foundational. Cham, Switzerland: Springer

Rowe, P. G. (1998). Design thinking. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Schaumburg, H. (2003). Konstruktivistischer Unterricht mit Laptops? Dissertation. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin. Internet-Dokument: http://edocs.fu-berlin.de/diss/receive/FUDISS_thesis_000000000914?lang=en [5.6.2015]

Segall, A. (2004). Revisiting pedagogical content knowledge: the pedagogy of content/the content of pedagogy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(5), 489–504.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14.

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22.