5. The Innovation: Collaborative Process Competence

NextGen.LX expands traditional instructional design in three key dimensions, which are explained below.

5.1 From individual design to collaborative processes

While traditional storyboards are created by instructional designers and then submitted for approval, NextGen.LX enables the collaborative design of learning processes via interdisciplinary teams. Its visual representation reduces cognitive complexity and makes learning design accessible even to non-designers, in line with research on visual complexity reduction, which shows that appropriate visual abstraction significantly increases cognitive efficiency without losing information (Kimelman et al., 1994; Stefaniak & Tracey, 2024).

This addresses a fundamental problem: expertise about relevant learning needs often lies with those who go through the process, not those who design it. By acting as a common, shared visual language, storyboards enable teams to articulate and help shape their own process skills; a form of externalization in the sense of Nonaka and building on Laurillard’s dialogue-based Conversational Framework.

5.2 From workshop-blueprints to essential organizational resources

Completed storyboards are not only implemented and archived, but also stored in libraries as organizational resources. These method, workshop and process libraries form a collective memory of successful learning processes, similar to organizational routines (Nelson & Winter, 1982), but explicitly formalized and thus transferable and scalable.

Teams can adapt existing storyboards, remix them and adapt them to new contexts. This enables scaling without standardization: it is not the identical process that is replicated, but the underlying design pattern that is repeatedly re-instantiated and adapted to the specific context. Process competence turns gradually into an organizational resource, independent of individual experts, coaches or external consulting agencies – indicating substantial corporate cost-savings.

5.3 Internalization of process-competence

The key difference to external consulting or training interventions is that the competence to design learning processes remains within the company. While classic organizational development is episodic and expert-dependent (workshops, facilitators, external consultants with proprietary methodological knowledge), social learning design strategically builds internal capacities. Success should become and remain replicable.

This confirms research findings on organizational learning competence as a strategic resource (DiBella & Nevis, 1998; Yeung et al., 1999): organizations not only develop specific new knowledge, but also the meta-competence to continuously design new learning processes; precisely the type of “learning to learn” competence that is considered the core of competitive advantage in uncertain environments.

5.4 Practical implications

The combination of visually structured learning activities, collaborative design and organizational storage addresses several critical scaling problems:

- Effective complexity management: Visual storyboards reduce the extraneous cognitive load (Sweller, 1988), the complexity that arises when designing demanding learning processes.

- The democratization of design: Process competence is no longer tied to formal instructional designers and is shifting to the area of tension between employees, teams and the organization.

- Organizational learning becomes a reality: successful processes become transferable process knowledge instead of the implicit know-how of individual teams

- Self-organizing teams: teams can design learning processes in a self-organizing manner without having to resort to external expertise

5.5 The integration with psychological safety

The joint design of learning processes on storyboards is itself a moment of collective learning, exchange and dialogue, and is therefore dependent on the conditions provided by the system’s trust-empowering structure. Without the implementation of psychological safety, dominant voices would shape the learning design, stakeholder issues would be outsourced to expert cultures, uncertain perspectives would go unheard, and the participatory character would collapse.

This is where system integration comes into play: storyboards are not just a method, but a manifestation of the underlying architectural principles, a place where status is decoupled, uncertainty is valorized, and collective intelligence is operationalized.

6. Organizational Implications

6.1 For medium-sized companies

Medium-sized organizations face a specific challenge. They are too large for informal coordination (customer agreements cannot be managed via a WhatsApp group), and they are too small for a dedicated learning and development infrastructure. In this regard, social learning design offers:

- A scalable organizational learning capability without a proportional increase in L&D staff or facilitation resources. The system structurally maintains learning conditions

- A cross-functional flow of knowledge without formal knowledge management overhead. Learning emerges from work, not separately from it

- Rapid competence building in uncertain domains where best practices do not yet exist, i.e. precisely where traditional training cannot take effect

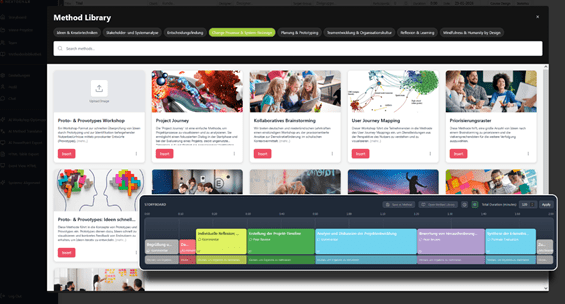

Screenshot 2: Stored are not curricular packaged knowledge assets, but processes and methods as a scalable organizational resource.

6.2 For transformation initiatives

In a recent study McKinsey (2023) shows that 70% of organizational transformation efforts fail, not because of a lack of vision, but because of an inability to learn quickly enough in the face of uncertainty. The Cynefin framework (Snowden & Boone, 2007) distinguishes between complicated problems (analyzable, solvable by experts) and complex problems (emergent, requiring probe- sense-respond). In complexity, learning speed determines success. At this point, it is also worth mentioning the ‘wicked problems’ of Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber, problems that cannot be clearly defined and have no clear solution.

Social learning design creates the conditions for organizations to think collectively at the pace that uncertainty demands. Recent research (Edmondson & Harvey, 2024) shows that organizations with structurally embedded learning conditions achieve transformations with a 3.5 times higher success rate than those that rely solely on cultural interventions.

6.3 The challenges of modern knowledge work

As knowledge work increasingly involves problems with no known solutions, what Schön (1983) calls “indeterminate zones of practice,” the ability to learn collectively under ambiguity becomes a primary competitive advantage. However, this requires an infrastructure that supports rapid hypothesis formation and testing, constructive integration of diverse expertise, rapid prototyping, and a mind shift from individual expertise to collective intelligence and accountable leadership.

6.4 Leadership in an AI-augmented social learning design environment

The role of personal and exemplary leadership is undergoing a fundamental transformation in AI-augmented learning environments and remains indispensable. While technological systems can provide infrastructures for social interaction, attitudes towards values and meaningful goals cannot be automated and must be embodied by the role model function of leaders (Avolio et al., 2009; Dinh et al., 2024). What social learning design proposes is a new organizational architecture in which leaders shape learning conditions, while AI-augmented work environments structurally support and maintain them.

6.5 From giving directives to enabling leadership

Edmondson and Mortensen (2023) show that successful leadership in complex, technologically mediated environments increasingly depend on the ability to create productive learning conditions rather than providing answers. This requires a shift from what Heifetz et al. (2009) refer to as ‘technical problem solving’ to ‘adaptive leadership,’ i.e., the ability to navigate uncertainty with teams and enable collective sense-making processes.

In AI-augmented environments, this means that managers no longer primarily define what should be learned, but rather design how collective learning becomes structurally possible. In their long-term study, Zenger and Folkman (2023) demonstrate that managers who act as ‘learning enablers’ achieve 2.3 times higher team performance than those who primarily act as ‘knowledge providers’.

6.6 Narrative leadership and storyboarding

Our approach to storyboarding is crucial in this context, as trust-building in organizations extends deep into individual life narratives and must remain connectable (Denning, 2024; Gabriel & Connell, 2010). Through narrative practices, leaders create coherence between individual horizons of meaning and organizational learning goals within the team.

Ibarra and Scoular (2023) show that narrative competence, the ability to frame learning processes as coherent development stories, is one of the most critical leadership skills in VUCA contexts. In this light, storyboards function as “boundary objects” (Star & Griesemer, 1989; Carlile, 2022) to integrate different perspectives while allowing for individual attributions of meaning. They create a common visual language that is psychologically safe enough to allow for inclusion, learning and contribution, and structured enough to ensure the ability to act.

Learning spaces as spaces for effectiveness

Critical to organizationally supported psychological safety is the recognition that learning spaces must always be spaces for effectiveness at the same time (Bandura, 2012; Parker et al., 2023). Trust building succeeds where teams not only learn theoretically, but also experience that their learning has consequences, that questions lead to better decisions, that doubts are addressed productively, and that experiments can solve real problems.

Recent research by Gino and Staats (2023) demonstrates that the integration of ‘learning cycles’ and ‘action cycles,’ simultaneous learning and action, increases organizational adaptability by 34–52%. In AI-augmented environments, managers can specifically design this integration: the system maintains the learning conditions, while leadership makes the connection between learning and impact explicit.

6.7 The role of the manager: curator and catalyst

Social Learning Design shifts leadership from hierarchical control to curatorial competence (Uhl-Bien & Arena, 2023). Managers not only identify constructive learning contributions, but also actively connect them with existing resources in the company or institution. They act as ‘knowledge connectors’ (Cross et al., 2023), recognizing patterns, creating synergies and integrating emerging insights into existing structures.

At the same time, they act as catalysts for well-moderated and guided teams. While the AI infrastructure structurally enables social security, managers embody this security through their behavior: they model learning orientation, normalize mistakes as sources of learning, and consistently signal that admitting uncertainty, quasi as “humble confidence”, signals professional strength, not weakness (Edmondson & Lei, 2024).

Screenshot 3: Slide by Dark Horse Innovation GmbH, Berlin from a leadership workshop: Besides the ability to listen, resource-orientation, clarity of goals and values, operation by feedback and the orchestration of diversity are mission-critical. We develop these requirements as integral part of the corporate social operating system.

6.8 The division of tasks between humans and machines

The key is a clear division of tasks between human leadership and technological infrastructure. AI takes on the consistent, tireless maintenance of structural conditions, evaluates epistemic value, synthesizes perspectives and moderates conflicts. Managers take on what machines cannot do (Huang et al., 2023): ethical judgement, empathic resonance, existential meaning-making, and the interpretation of what is organizationally significant.

This new hybrid architecture, which integrates technological infrastructure with human leadership, enables scaling without dehumanization. It thus addresses a central limitation of previous approaches, as cultural change without structural support inevitably fails due to a lack of consistency, while technological systems without human leadership remain meaningless (Jarrahi et al., 2023).

6.9 Practical implications for leadership development

This new leadership role requires specific competencies that are underrepresented or not represented at all in traditional leadership development programmes (Day et al., 2023): On the one hand, this is narrative competence, the ability to frame learning processes as coherent development stories and to connect individual meaning with organizational goals. This requires appropriate curatorial and editorial skills to recognize patterns in emerging learning processes and link them to existing organizational resources.

Added to this is structural design competence, the ability to adaptively design learning conditions as learning designers as system properties. In the role of team leads, this requires practice in adaptive moderation, navigating teams through uncertainty without prematurely dissolving productive tension.

Social learning design enables managers to not only learn these skills in the abstract, but to develop them directly in the design of real learning processes; an approach of ‘learning by designing’ that integrates competence development and organizational effectiveness.